Edition 6 - May, 1999

Edition 6 - May, 1999 |

Molecular microbiological tools for food industry |

PFGE - Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is the most discriminatory DNA-based typing method. Intact chromosomal DNA is isolated in situ, employing agarose plugs and is digested with infrequently cutting restriction endonucleases. Large genomic fragments are separated by cyclically altering the orientation of the electric field during electrophoresis. Macrorestriction genomic fingerprinting by PFGE is an indicator of clonal origin of strains. One of its uses is the identification and tracing of starter strain(s) during food manufacture, to detect contamination sites of spoilage organisms during processing (HACCP), or to check the authenticity of proprietary strains. Lanes 1 and 8, molecular weight marker DNA (Staphylococcus aureus); lanes 2, 3 and 7, Enterococcus durans strains of different clonal origin; lane 4, Enterococcus hirae; lane 5, Enterococcus flavescens; lane 6, Enterococcus faecium. |

Long before the human awareness of the existence of micro-organisms, bacteria, fungi and yeasts were playing an important role in food preparation and storage. The Babylonians (7000 BC) and Egyptians (3000 BC) used them to prepare beer and milk products. Humans have taken advantage of - and have been plagued by - micro-organism activities in foods for thousands of years.

Many foods, such as ripened cheeses, fermented sausages, beer, wines, coffee and cacao, owe their production and characteristics to the fermentative activities of micro-organisms. In addition to being made more shelf stable, fermented foods have aroma and flavour characteristics that result from the fermenting organisms. Lactic acid bacteria are used worldwide in the manufacture of dairy products, such as cheeses, yoghurt, kefir and sour cream. The action of yeasts, and in particular Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is well known in the fermentation of wine and beer. Fungi are involved in the processing of cheeses (e.g. Penicillium roqueforti) or are a direct source of proteins in, for instance, Asian fermented products such as soja sauce, tempeh (e.g. Rhizopus), and the recently launched quorn. Starter cultures are used to initiate the fermentation process. Many of the cultures are complex mixtures for which the production conditions are precisely defined. Nowadays, molecular techniques provide an outstanding tool for the detection, identification and characterisation of micro-organisms involved in these processes.

Micro-organisms can spoil or infect our food. To prevent or retard microbial spoilage, it is important to consider those mechanisms that our food sources, plants and animals, have developed to defend themselves against the invasion and proliferation of micro-organisms. Some of these intrinsic parameters - such as pH, moisture content, nutrient content or antimicrobial constituents - are an inherent part of plant and animal tissues and may remain effective in fresh foods. The extrinsic parameters of foods are those properties of the storage environment that affect both the foods and their micro-organisms. These factors include storage temperature, relative humidity, atmosphere and the presence of other micro-organisms. These parameters, and the microbiological condition of the raw product at the time of processing, often determine the total counts of spoilage bacteria, which may not exceed certain levels. Molecular characterisation methods can be used to obtain more information about contamination and dissemination of micro-organisms in different parts of the food chain.

The incidence of micro-organisms in foods is also determined by the hygienic status of the processing steps. In some cases pathogenic organisms may enter and cause poisoning of the food product. A number of moulds produce mycotoxins, which can be mutagens, or carcinogenic, or display some specific organ toxicity. Several bacterial species may cause gastroenteritis, and particular taxa may be responsible for outbreaks of botulism (Clostridium botulinum), listeriosis (Listeria monocytogenes) and other diseases. DNA techniques can identify the disease-causing agent and trace the dissemination of the pathogen in the food process and the environment (see box: Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points).

The examination of foods for the presence, types, and numbers of micro-organisms (and/or their metabolites) is of major importance to food industry.

There are three major applications:

(i) identifying the bacterial flora of starter cultures and foods,

(ii) determination of the total numbers of bacteria in food samples,

(iii) detection of particular types in food products or the environment.

A variety of routine methods is available, along with newer developments that are more precise, accurate and rapid than their predecessors. In this paper, we will consider the possible contribution of specialised research microbiology labs, such as those in the BCCMTM consortium. Routine diagnostic tests are mainly based on growth characteristics of an organism on a selective medium, recognition of microbial antigens by monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies, biochemical and phenotypic properties, antibiotic susceptibility, and general features like colour, colony form and odour. The more recent techniques are based on molecular methods.

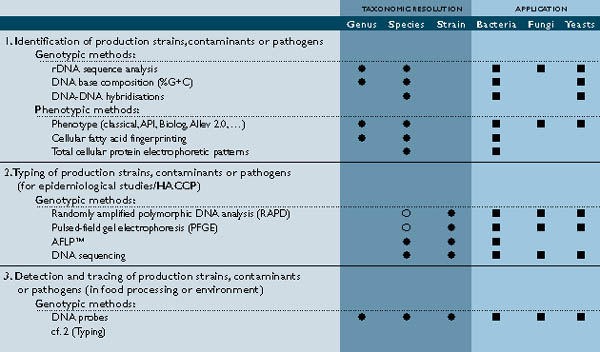

These include tools such as 16S rDNA sequencing and subsequent DNA homology, which studies allow the classification and identification of any isolate. Extensive phenotypic and chemotaxonomic analyses may be performed in order to describe and differentiate (new) taxa. All these modern technologies and expertise are available at the specialised BCCMTM research laboratories, meeting the needs of the modern food microbiologist (see table). Additionally, large databases ensure fast, reliable results.

The introduction of molecular biological techniques has also yielded a variety of DNA-based typing methods, which can even discriminate between isolates of a given species. These data can be used for epidemiological purposes and may provide insight into the dissemination and persistence of spoilers and/or pathogens in the environment. Discrimination between coincident but independent infections and epidemics caused by a single isolate is a major concern, which affects the preventive and hygienic measures to be implemented. Genetic typing methods can be divided into different categories depending on the technical aspects: DNA sequencing, restriction endonuclease analysis of plasmid or genomic DNA (e.g. RFLP, PFGE), probe-based technologies and PCR-based technologies (such as RAPD, AFLPTM). These methodologies can be developed and adapted by BCCMTM, according to the specific requirements of the food industry (see table).

References:

Jay J.M., 1996. Modern Food Microbiology. Chapman & Hall, New York.

Vandamme P., Pot B., Gillis M., De Vos P., Kersters K., and Swings J., 1996. Polyphasic taxonomy, a consensus approach to bacterial systematics. Microbiol. Rev. 60, 407-438.

Contacts

Home |

Contents Edition 6 - May, 1999 |

Next

Article Edition 6 - May, 1999 |